The Origins of Caste: Social Order in the Vedic Age

RESEARCH

7/21/20253 min read

[Early History: Pre-Vedic]

During the second millennium BCE, groups of Indo-Aryans began migrating through the Hindu Kush mountains and into the Indian subcontinent (Bentley 75). Archaeological evidence suggests that they practiced agriculture on a small scale, with a primary focus on pastoralism (Singh, 124). The Indo-Aryans did not have a centralized state or a common government, but instead formed hundreds of chiefdoms. Kinship was the basis of the political and social structure, with loyalty pledged to the jana, or tribe (Prasad, 11). They probably had a reasonably simple society consisting of headers and cultivators led by a rajan (chief). His main task was to protect his people and lead them to victory in war (Singh 448).

In the absence of any centralized state or officiated legal code, the Vedas reflect a hostile landscape where groups frequently quarreled over land and resources. The Battle of the Ten Kings, for instance, was a historic conflict between King Sudās’s Bharata tribe and a confederation of ten other tribes. Featured in the Rig Veda, not only did Sudās’s victory and subsequent alliance with the Purus establish the hegemony of the Bharata tribe, but it also marked an early instance of political consolidation after the coalition formed the Kuru dynasty (Doniger, Book 7).

[The Vedic Period]

Coinciding with their reliance on agriculture, the Indo-Aryans established permanent settlements, replacing tribal structure with more formal institutions. In the mountainous regions of northern India, councils of elders won recognition as the principal source of political authority. For the most part, though, establishing kingdoms became the conventional mode of political organization. As civilizations became increasingly complex in such a hostile environment, some groups of Indo-Aryans found it necessary to develop a system capable of maintaining order (Bentley, 76).

[The Caste System]

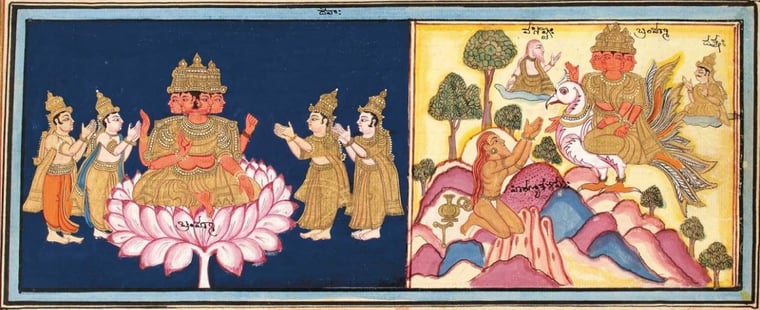

Around the first millennium BCE, the caste system was primarily known for delineating roles and occupations throughout society. Indo-Aryans used the term varna, a Sanskrit word for “color,” to classify people into four groups: brahmins (priests), kshatriyas (warriors and aristocrats), vaishyas (cultivators, artisans, and merchants), and shudras (peasants and serfs) (Bentley 77). Found in the Rig Veda, the Purusha Sukta is the earliest hymn that alludes to class structure (Doniger, Book 10). This hymn postulates that each varna emerged from a primordial being named Purusha. According to the text, brahmins came from his mouth, kshatriyas came from his arms, vaishyas came from his thighs, and shudras came from his feet (Majumdar 388; Singh, 476). Notwithstanding the hymn’s mythological concepts, the text indicates a hierarchy, with the brahmins located at the top and the shudras situated at the bottom

[Laws of Manu]

Although the Laws of Manu emerged later in the Vedic period, they significantly altered the interpretation of the caste system. Composed during the first millennium, the Laws of Manu (“Manusmriti”) were a set of provisions outlining appropriate behavior within society. By purportedly explaining the origins of our universe, the manuscript presents a quasi-theological foundation as a precursor before defining dharma and detailing individual obligations. Dharma encompasses duty, law, and righteousness, all of which seemingly contribute to the social order. In addition to the former, the text also specifies regulations on education, marriage and household rituals, permitted and forbidden occupations, rules of caste interaction, and moral conduct (Bühler).

Indeed, the caste system had functioned as it was intended, since the institution managed to endure for some time. Despite the institute of social order, by the end of the Vedic period, many began to deviate from and disobey their primary duties. Internal strife gradually overshadowed the social order, and by 500 BCE, the Vedic Age had come to an end. However, even though political power changed hands, the caste system experienced a resurgence due to its enduring role in religious, social, and economic life.

(National Mission for Manuscripts)

(Worship of Brahama)

Primary Sources

Georg Bühler, The Laws of Manu (Central, Hong Kong: Forgotten Books, 2008).

“Memory of the World.” National Mission for Manuscripts, www.namami.gov.in/memory-world.

Rig Veda in English (Internet Archive, 2018), 70 and 590.

Secondary Sources

Prasad, Pallavi. 2018. “Tribes and Tribals in Early India.” Researcher: A Multidisciplinary Journal of the University of Jammu 14, no. 2 (2018): 78-81. Researchgate.net

R. C. Majumdar, History and Culture of the Indian People: The Vedic Age, vol. 1 (Delhi, India: Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, 2015), 388.

Upinder Singh, A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century (Noida, India: Pearson, 2019), 447-448.

Tertiary Sources

Worship of Brahma. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. August 23, 2006. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Worship_of_Brahma_and_Brahma_on_his_Swan_in_the_Mountains_with_Ascetics%286125144826%29.jpg.