Nubian Society: Settlement and Burial Sites

RESEARCH

7/22/20253 min read

Early History: Pre-Kerma

Beginning around the fourth millennium, the region of Nubia was inhabited by a civilization dubbed the “A-Group.” Scholars have determined that they were semi-nomadic herders and agriculturalists who also supplemented their livelihoods by fishing, hunting, and gathering (Galland et al.). At its height, circa 3100 BCE, the region saw one of the earliest attempts at state formation. Unfortunately, early in the third millennium, the A-Group disappears from the archaeological record due to the rise of Egyptian dominance in the region (Emberling and Williams, 123).

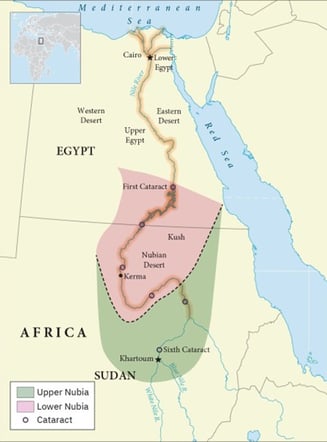

Four hundred years later, semi-nomadic pastoralists termed the “C-Group” people inhabited Lower Nubia, marking a reorganization of Nubian society (Emberling and Williams, 155). Unfortunately, the Egyptian presence in the north forced Nubians to concentrate their efforts at political organization farther south in Upper Nubia. Leaders began to centralize authority, organize construction labor, and control regional trade corridors. By 2500 BCE, Nubian leaders established the Kingdom of Kush with its capital at Kerma (Bentley et al., 51).

Kingdom of Kush: Kerma Culture

It is during the Early Kerma period (c. 2500—2050 BCE) that sociopolitical institutions and socioeconomic distinctions appear within the archaeological record. Over the next five centuries, Kerma expanded from a few habitations of round post buildings into a larger and more complex society, featuring palaces, ceremonial structures, and systems of defense. However, alongside these developments, modest buildings and tombs persisted, giving the impression of social stratification (Schrader and Smith, 7). Several buildings for worship and a ceremonial palace were built on the site of a former citadel with massive fortifications.

Other notable structures include a palace and a large circular hut, which is understood to have functioned as an audience room for kings. The capital of Kerma also contained religious structures known as a Deffufa. Located near these temples were storage rooms, workshops, and even, as defensive measures, for the troops. The architecture at Kerma suggests the presence of a centralized form of governance and an administrative elite. Likewise, the construction of massive public works indicates the presence of leadership capable of mobilizing labor and resources on a large scale (Raue, 413).

Burial Sites

Archaeological excavations at Kerma have uncovered evidence of social stratification, and radiocarbon dating confirms that these changes in funerary rites occurred between 2300 and 2150 BCE. During this time, tombs began to differ in size and scope, with some of the more elaborate graves measuring sixty-six feet in diameter (Schrader and Smith, 10). Tumuli found to have multiple burials also became more prevalent (Emberling and Williams, 220). This period also marks the emergence of the first elites alongside increased trade, as corroborated by larger and richer graves with goods such as bronze mirrors, assortments of jewelry, and bucrania (Emberling and Williams, 220; Tumuli Photograph).

Several tombs were also endowed with bows or shepherd staffs (Schrader and Smith, 10). The presence of archery equipment and the shepherd staffs evokes the importance of societal roles in Nubia. Further research on the skeletons in these graves reveals that males exclusively formed the archers, and shepherd staffs were only found in female graves, reflecting the importance of specific roles (Schader and Smith 216). In addition, richer tombs might have contained sacrificed dogs or sheep, which were often found at the feet of the deceased. In Nubian society, references to war, the hunt, and pastoralism undoubtedly carried significant symbolic meaning for the Kingdom (Emberling and Williams, 220).

As early as the fourth millennium BCE, Nubia’s A-Group demonstrated complex subsistence strategies and early state formation, which were disrupted by the expanding power of Egypt. The subsequent emergence of the C-Group and the establishment of the Kingdom of Kush marked a pivotal shift in Nubian society when leadership centralized in Upper Nubia, laying the foundation for one of Africa’s earliest states. As reflected in the archaeological record, Kerma reflected a complex sociopolitical structure, evidenced by its monumental architecture, organized labor systems, and stratified funerary practices.

(Robert Harding)

(Map of Nubia)

Primary Sources

Matthieu Honegger, “The Archers of Kerma: Warrior Image and Birth of a State,” Sandpoints.org, 2018, https://pages.sandpoints.org/dotawo/article/honegger.

Harding, Robert. Photograph. The Western Deffufa. 2020. Archaeology Magazine. https://archaeology.org/issues/september-october-2020/features/sudan-kerma-nubian-kingdom/

Dietrich Raue, Handbook of Ancient Nubia Volume 1. (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2019), 413.

Secondary Sources

Geoff Emberling and Bruce Beyer Williams, The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 123-220.

Manon Galland et al., “11,000 Years of Craniofacial and Mandibular Variation in Lower Nubia,” Scientific Reports 6, no. 1 (August 2016), https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31040.

Sarah Schrader and Stuart Tyson Smith, “Archaeology of the Kerma Culture,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, (2021): 7-216, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.1071.

Tertiary Sources

Jerry Bentley, Herbert Ziegler, and Heather Salter, Traditions and Encounters: A Global Perspective on the Past. 7th ed. (New York, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2020), 51–391.

Map of the Kingdom of Kush. Photograph. Elon.io. 2025. https://elon.io/learn-world-history-1/lesson/9.3.1-the-origin-and-rise-of-the-kingdom-of-kush#fig-00001.